Editor’s

Letter

If 2020 has shown us anything it is that nothing is certain and whilst it is impossible to predict what will happen moving forward in relation to Covid-19, we can assume that the foodservice industry will continue to be impacted for the foreseeable future and beyond.

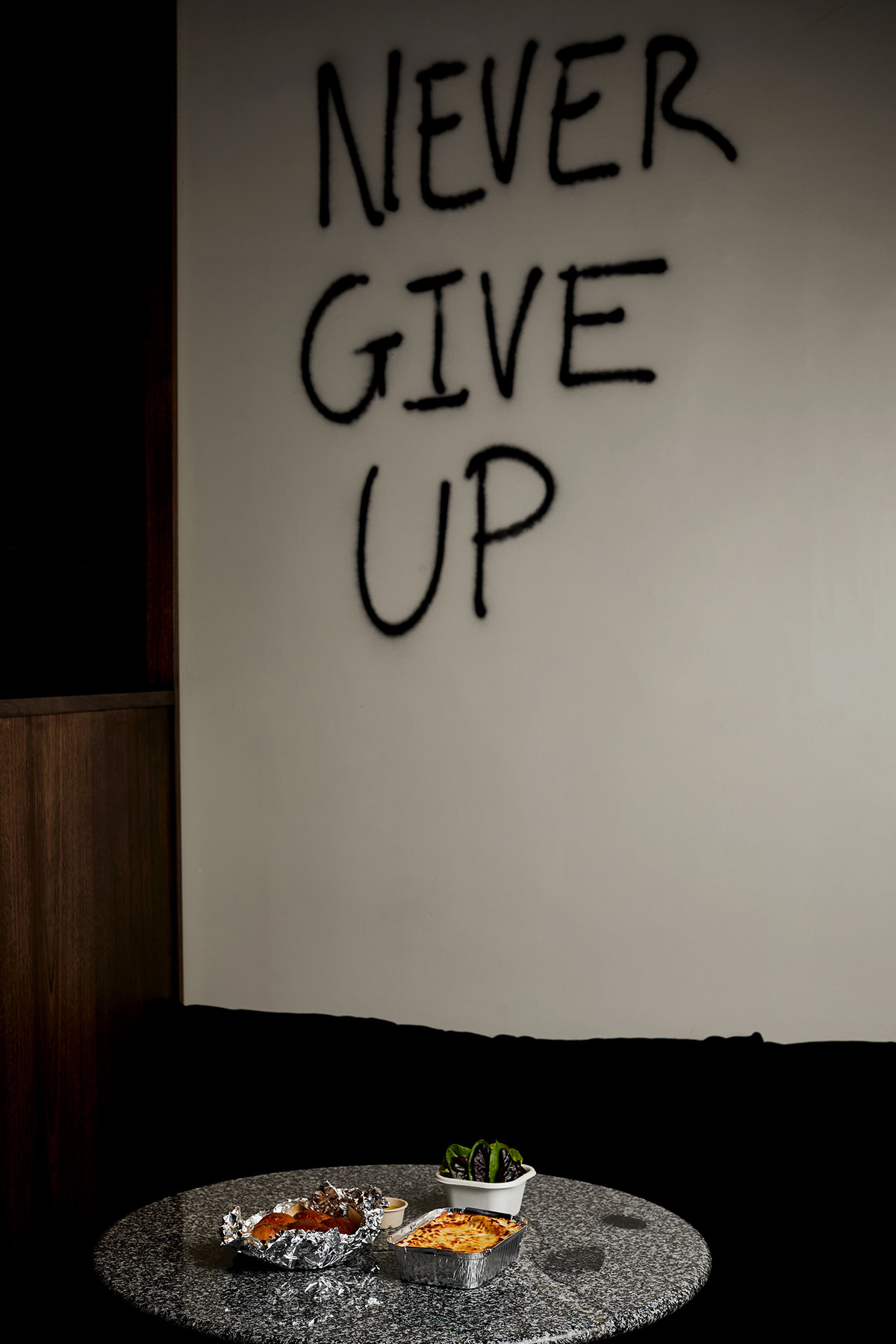

The foodservice community has demonstrated its resilience – your determination, your diligence and camaraderie are the true measures of hospitality. But if Covid-19 has taught the industry anything, it is that the model needs to adapt, offerings need to diversify and those with the ability to change will be the ones that survive.

The Australian red meat industry has itself faced a raft of challenges with foodservice shutdowns not only locally but around the world in every export market. Increased demand at a retail level somewhat softened the blow but demand for mince products led to carcase imbalances as premium cuts diverted from foodservice and into mince and sausages.

Moving back through the supply chain, livestock prices are at record highs as producers seek to restock herds and flocks after widespread rain brought some reprieve to long term drought conditions – meaning less livestock are available for processing.

The last few months have given me an opportunity to rethink what we bring you in our quarterly publication, to reconsider what matters and why. We have done some adapting of our own and this issue brings with it some exciting changes.

Firstly – I’m proud to welcome two incredible contributors to the Rare Medium family, each with their own dedicated sections. Pat Nourse, one of Australia’s most accomplished food journalists, takes on our new People | Places | Plates section – sharing the stories of chefs, venues and menus; while industry legend Mark Best brings us his Spotlight On section – an exploration of various components of the Australian red meat supply chain.

Our new What’s Good in the Hood section reflects the importance of community dining and celebrating neighbourhood favourites. First up we explore Sydney’s Inner West with the fabulous Myffy Rigby. If anyone is going to show us around town then it may as well be the editor of the Good Food Guide!

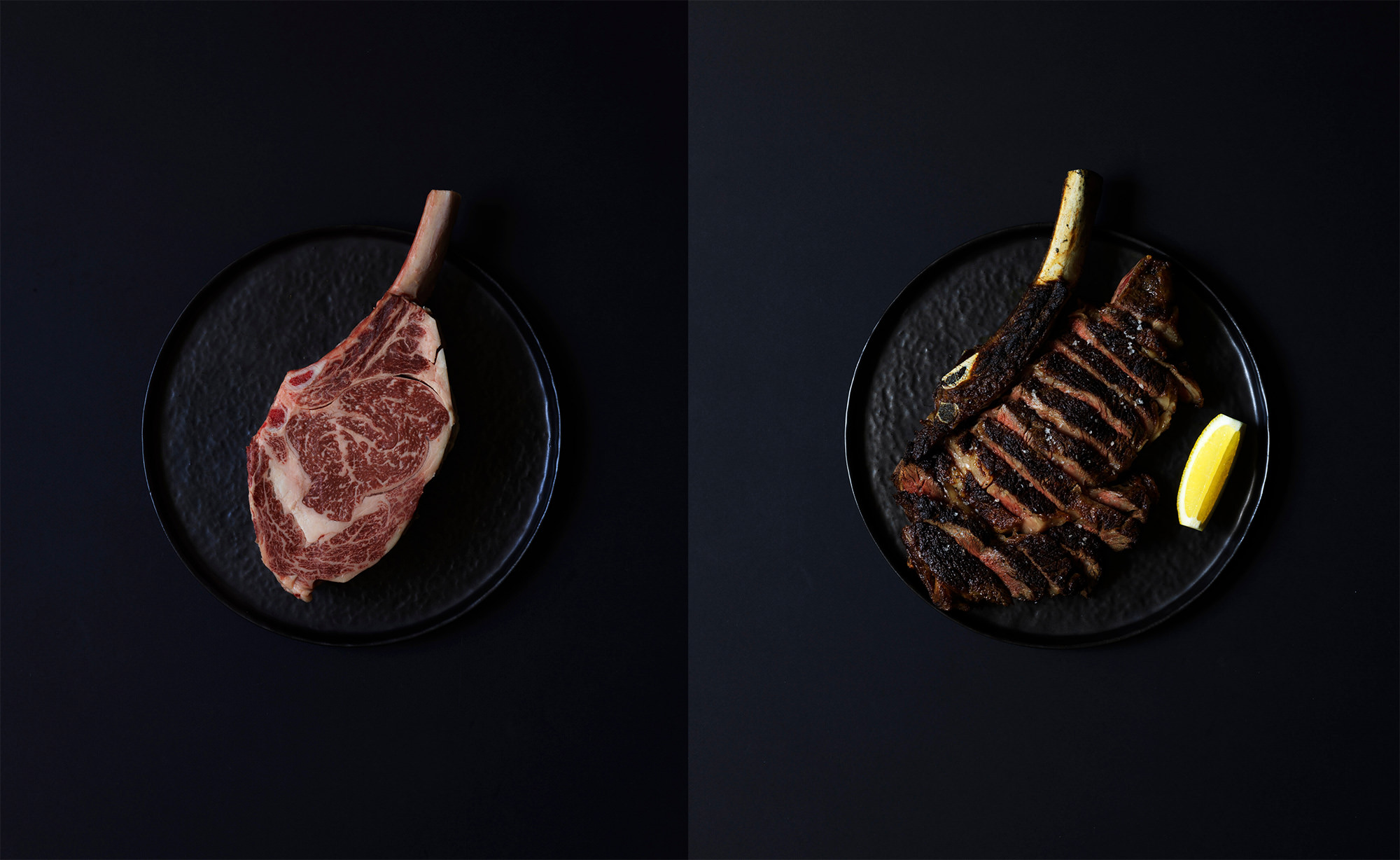

We also have a new Cut Two Ways section – featuring a different cut each time cooked by two different chefs and our Young Guns section that explores the stories of young professionals through the red meat supply chain.

The value of supply chain relationships has never been more apparent and I look forward to continuing to connect you with our wonderful Australian red meat producers, to grow and prosper together with whatever comes next.

Following your journeys over the last few months has at times been heartbreaking but more often than not it has been empowering. I hope that the stories of this issue inspire you as you have me – as together we come to terms with this strange new world.

Mary-Jane Morse

Meat & Livestock Australia

[email protected]

@_raremedium

Copyright: this publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA).