The festive season is snapping at our heels and it is always the busiest time of the year for foodservice with long lunches, work events, Christmas parties, New Year’s celebrations – any excuse really to indulge in some world-class hospitality at venues across the country.

In this issue I wanted to explore what celebrations looked like in a range of cultures and cuisines and one thing is clearly evident; food is almost always at the centre of celebrations – from the cooking through to the consumption, it is about coming together to share experiences and connect.

It’s memories of New Year’s Day in Mauritius that come to the fore when Pat Nourse chats with Nagesh Seethiah at his restaurant Manze in North Melbourne. Pat writes – “New Year’s day is big in Mauritius, bigger than Christmas Day, and a big celebration called for a goat or two, with the families making a day of it and everyone pitching in to cook every part of it.” Read more about Nagesh, Manze and celebrating Mauritian style in Pat’s People Places Plates section.

Meanwhile Mark Best explores The Taco-lypse – Australia has well and truly hit its stride in the taco-stakes, evolving from Old El Paso tex-mex to taqueria pop-ups in the Rocks from acclaimed Mexican American chef Claudette Zepeda. Mexican culture embraces celebration perhaps like no other, as Claudette says “Mexico is a nation of immigrants and their ingredients, and I think we are programmed to share and celebrate our similarities and differences.” There ain’t no party like a taco party and in this story Mark seeks out some of the best tacos in Sydney.

Auburn in Sydney’s inner west is a suburb quite unlike any other and Myffy Rigby explores its incredibly diverse cuisines with relish in this episode of What’s Good in the Hood. From Lebanese breakfast to Turkish mix plates; Uyghur meat pies to Afghani dumplings; East African platters to Peranakan curries – it’s a celebratory smorgasbord like no other.

Ross Magnaye tells me that to him, food has always been part of family and that the Filipino way of celebrating is always heavily centred around food. Magnaye is taking his Filipino heritage and sharing it with the world at Serai in Melbourne’s CBD – you can expect loud music, happy people, natural wines and modern Australian food with Filipino twists. If anyone can throw a party, it’s Ross Magnaye – read all about it in my Young Guns section.

Did you know October is Goatober? Well now you do. We teamed up with chefs Ibrahim Kasif, formerly of Turkish favourite Stanbuli and now head chef at Beau; and restaurateur and former Masterchef star Minoli De Silva of Ella in Darwin – for our Cut Two Ways section – and you guessed it, they are cooking goat. Be inspired to give goat a go with these two deliciously different dishes.

Until 2023 – be safe, be well and keep being inspired by Australian beef, lamb and goat.

Mary-Jane Morse

Meat & Livestock Australia

[email protected]

@_raremedium

Copyright: this publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA).

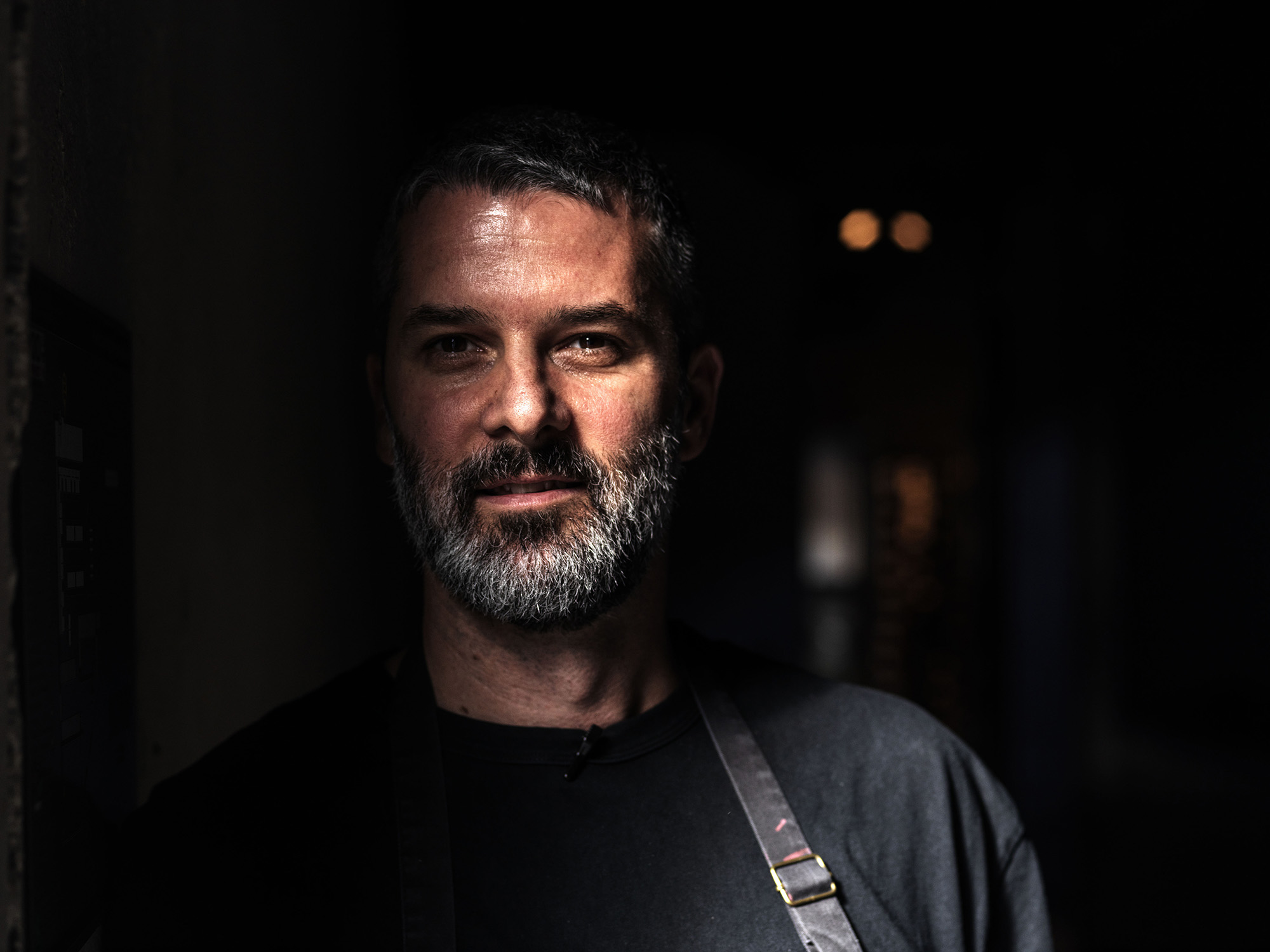

It made perfect sense to bring in the big guns to help us navigate Perth’s bubbling foodservice scene – a passionate advocate for all things WA, and a man with much more than his finger on the pulse; quite possibly the beating heart itself.

It made perfect sense to bring in the big guns to help us navigate Perth’s bubbling foodservice scene – a passionate advocate for all things WA, and a man with much more than his finger on the pulse; quite possibly the beating heart itself.

When Meat & Livestock Australia asked me if I wanted to be guest editor of the Perth edition of Rare Medium that you’re reading, I said yes straight away. Not because it’s been a while since Rare Medium came to Western Australia and I wanted to make sure they were talking to all the right people. And not because it meant working with talented pals Myffy Rigby, Jason Loucas, Anthony McFarlane and Rare Medium editor Mary-Jane Morse to share Perth’s best with the rest of Australia. (Having said that, linking up with an all-star crew certainly didn’t suck; nor does sharing page space with Australian food heavyweights Pat Nourse and Mark Best).

When Meat & Livestock Australia asked me if I wanted to be guest editor of the Perth edition of Rare Medium that you’re reading, I said yes straight away. Not because it’s been a while since Rare Medium came to Western Australia and I wanted to make sure they were talking to all the right people. And not because it meant working with talented pals Myffy Rigby, Jason Loucas, Anthony McFarlane and Rare Medium editor Mary-Jane Morse to share Perth’s best with the rest of Australia. (Having said that, linking up with an all-star crew certainly didn’t suck; nor does sharing page space with Australian food heavyweights Pat Nourse and Mark Best).