People Places Plates

Back to contents

Ben Russell

Rothwell’s Bar & Grill

When it comes down to it, a lot of comfort is about familiarity. Dad’s curry. Mum’s soup. The smell of something cooking away on the stove or in the oven at your nan’s house when you’re a kid, or the things you ordered at those first restaurants you visited with the family.

There’s certainly more than a few Australians today who get a bit misty-eyed thinking about the heyday of the prawn cocktail and the steak Diane because they were there for it, living in that time and place. But what about the familiarity of dishes that didn’t get cooked in your house, or the other places your family went to eat? How do you explain their hold on the public imagination?

The Beef Wellington at Rothwell’s Bar & Grill in Brisbane is a case in point. It’s a dish of British/French origin that has been around for at least a hundred years. Why exactly is it enjoying an unlikely renaissance right now at the hottest restaurant in the humid, subtropical climes of the Queensland capital?

For Ben Russell, there’s no mystery to its success: it’s about quality and it’s about deliciousness. A chef who has worked right across the spectrum of the familiar and the unfamiliar in his life in restaurant kitchens, Russell takes the view that the magic of dishes like Beef Wellington lies in taking combinations of ingredients and techniques that have stood the test of time, and honouring them with cooking that is all about quality produce and careful, honest preparation.

The Beef Wellington at Rothwell’s Bar & Grill, Brisbane.

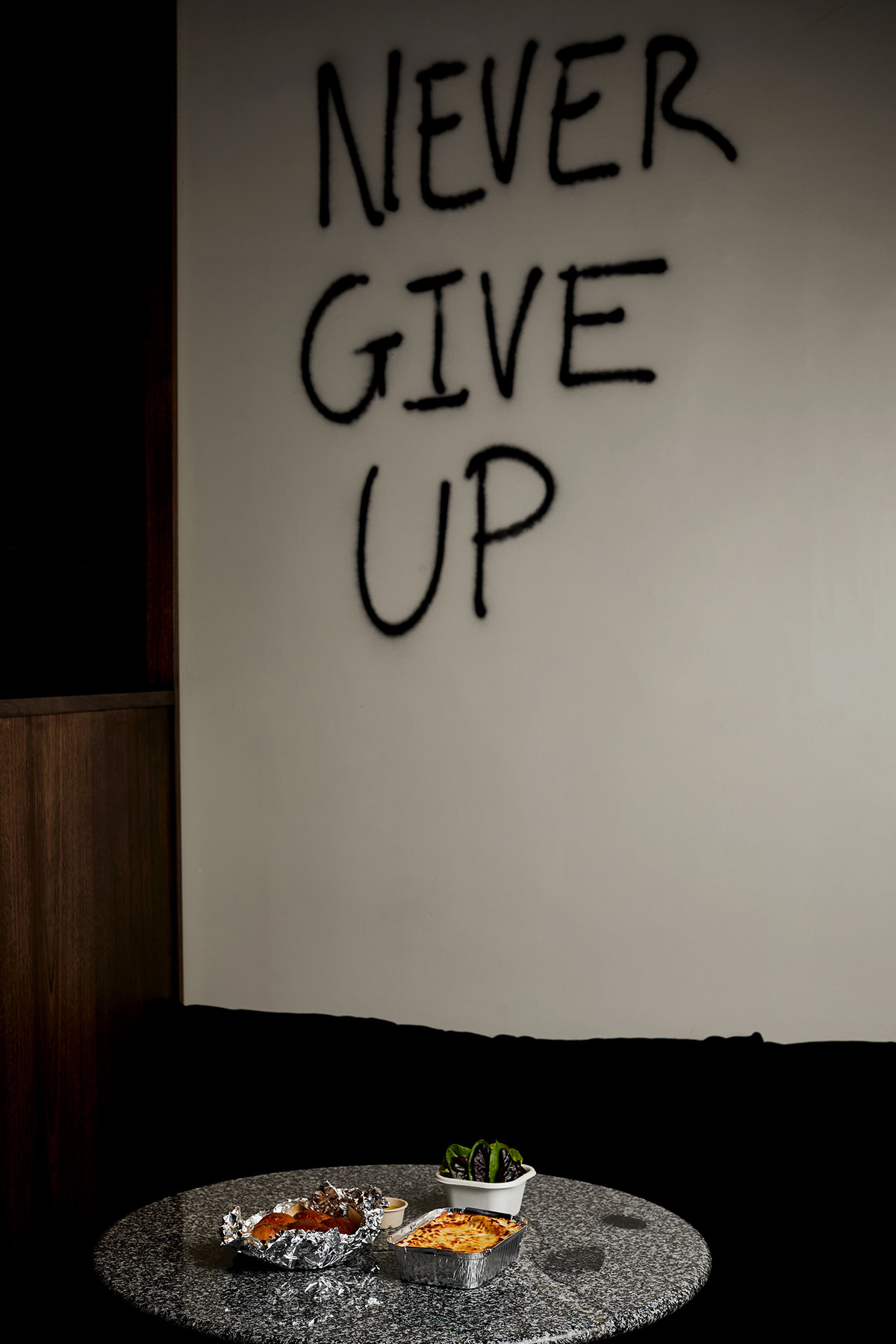

On his menu at Rothwell’s there’s a French onion dip among the appetisers, and an entrée that brings together prawn, avocado, lettuce, and cocktail sauce. There’s Caesar salad blessedly free of grilled chicken. There’s Martinis and Bloody Marys at the bar, there’s a seafood platter to share, and there’s trifle and madelines for dessert. But it’s about timeless elegance and not a retro trip.

“It’s not about trickery here,” says Russell, “you know what you’re in for.” There’s no side-eye, no riff or remix – the bat is played straight, and the result is dishes that surprise and delight with their freshness and immediacy.

A beautifully lit room, with lots of marble, big chandeliers, dark-green leather booths and well-chosen jazz, makes for a fitting backdrop. With Dan Clark, the operator behind 1889 Enoteca and one of Australia’s savviest wine importers, backing the place, the food is complemented by a list rich in treasures – 18-year-old Krug and JJ Prum riesling on by the glass, magnums and jeroboams of Gravner and Cornelissen, and a sea of Burgundy.

The thing about classics is that they’re classics for a reason. “They may not always be prepared in the best possible way from the finest possible ingredients but it’s easy to understand their appeal,” write Simon Hopkinson and Lindsay Bareham in their book, The Prawn Cocktail Years. “If one bothers to prepare these and other dishes that predate the whim of fashion in food then it is a revelation how good they can be.”

Rothwell’s Dining Room: a big-city restaurant replete with marble, chandeliers, dark green leather and jazz on the stereo.

Which brings us, of course, to Ben Russell’s Beef Wellington. Here’s how he does it.

First, the beef fillet. Russell goes grain-fed because he thinks it’s firmer and holds up a little better in the way it cooks in the Wellington, which essentially steams inside the pastry. He sears the beef in a hot pan, brushing it liberally with Dijon mustard.

Next comes the mushroom duxelles – rather than slicing and pan-frying the mushrooms in batches, Russell roasts them off whole in a pot to cook all the water out of them and to intensify their flavour, then blends them and presses them for a couple of hours to squeeze out any remaining moisture.

Then the crêpes: flour, eggs, milk and a little bit of beurre noisette. He lays a crêpe out on the bench, layers on about a centimetre of the mushrooms, then the beef fillet. It’s rolled, wrapped in clingfilm and goes into the fridge for a couple of hours to set before he wraps it in a layer of butter puff pastry, egg-washes it, and then adds another layer of lattice pastry, and more egg wash.

Then it goes into the Rational at 200 degrees till it hits an internal temperature of 35 degrees. Wrapped as it is in pastry, the meat comes up to a nice medium rare as it rests. The thickness of the pastry is the tricky part, Russell says: if it’s too thick, it won’t cook through before the beef is done.

It’s served with a red wine sauce – red wine and port reduced with lots of shallots and thyme on a veal-stock base.

“We carve it in half in the kitchen, and it goes out on a large oval plate looking very decadent with an antique silver jug of the sauce on the side – it smells rich and warm with the puff pastry and the mushrooms and the red wine sauce.”

“When you’re eating it, even though that layer of Dijon is just brushed on, it’s something that I think is a pleasant surprise. Fillet steak, mushrooms and pastry are not necessarily hero ingredients on their own but together they’re sensational. It’s an experience to savour. It’s a good time.”

To drink? Dan Clark imports some pretty radical wines but he says he likes to pour classics with classics. “Top-end Yarra Valley and Margaret River cabernet work really well with the Wellington. Cullen, Moss Wood, Wantirna. Or brighter shiraz – Dune in McLaren Vale and Izway from the Barossa Valley do the job nicely as well.”

To game it out even further, Russell suggests Martinis at the bar beforehand, then settling into a booth for some raw seafood and oysters or a crab salad, maybe the tagliatelle with sea urchin, then your Wellington and sides to share, maybe a tarte tatin or a crème brulée afterwards. “And then we have an Armagnac trolley, so if you want to get really comfortable, we’ve got bottles there dating back to the 1920s. And that’s your Rothwell’s experience.”

Ben Russell grew up in Burnie in the northwest of Tasmania. His first cooking job was at 18 at the fabled Jimmy Watson’s on Lygon Street in Melbourne, a third-generation business with a focus on wine. It was his next job, though, that made him the chef he is today.

Run by British chef Donovan Cooke and Melbourne chef Philippa Sibley, Est Est Est was famously uncompromising. Cooke was a protégé of Marco Pierre White, and he and Sibley shared a vision for a restaurant that hewed firmly to the traditions of the French restaurants where they’d worked in Europe.

They made pot-au-feu of beef, oxtail terrines with root vegetables and grain mustard. There was always a pigeon dish on the menu, alongside stuffed and braised pig’s trotters à la Pierre Koffmann, and Pithiviers of quail and foie gras, and every scrap of it was made by hand, from the puff pastry down.

“Six double shifts a week was our roster, so 14 hours a day, six days a week,” says Russell. The kitchen was not well equipped – at first it didn’t even have a coolroom. “We’d buy in everything every day, get there in the morning and crack on, making everything fresh every day from scratch, no room for error. If something went wrong, there was no back-up plan.” As intense as it was, he says, it was also what he’d been searching for.

“I was looking for something that was all-consuming. There was no time for anything outside that job.” It was unbelievably gruelling, but, looking back, he says, it crammed 10 years’ worth of learning into just three years.

Ben Russell at Rothwell’s Bar & Grill.

After he left Melbourne, Russell bought a one-way ticket to Paris. He went south, immersing himself in the culture of southern France, and cooking on yachts on the Mediterranean. Here he reacquainted himself with daylight, joined the dots with the produce he saw in the markets, and cured himself of the urge to push everything through a chinois.

Coming back to Australia three years later, Russell approached Matt Moran for a role at Aria in Sydney. At Aria, he found scope, support and structure. A place with both coolrooms and back-up plans, and somewhere a young chef could learn about the business of running restaurants beyond the knives-and-fire side of the operation. He flourished under Moran’s mentorship, and Moran in turn tapped him to lead the company’s expansion into Queensland, with Russell opening Aria Brisbane for them in 2009.

Under his care, the restaurant ran for 10 successful years, and signalled a watershed moment in Brisbane for finer dining. It also gave Russell the opportunity to find his own sound. Having opened leaning heavily on the dishes for which Matt Moran was known – confit pork belly with apples, Peking duck consommé – it shifted over the years to less butter and more tomatoes and olive oil, an affinity with the flavours of the Mediterranean that can be seen in Russell’s cooking to this day.

Classics for a reason – the steak tartare at Rothwell’s Bar & Grill.

Our times shape our restaurants. For Ben Russell and Dan Clark, the Rothwell’s conversation began during the pandemic, and this shaped its direction. “Dan and I have both been in the game long enough that we wanted to make sure we were going to be commercially viable in the long term,” Russell says. They were talking about a big-city restaurant, and about longevity. All the places they shared as points of reference – The Savoy Grill and The Wolseley in London, Balthazar in Manhattan among them – had all been running for many years.

Then there was the site. Thomas Rothwell hung out his shingle as a tailor here on Edward Street in the heart of Brisbane in 1885. When Clark and Russell looked to register “Rothwell’s” as the name of the restaurant, they found it was already registered by another business. Just adding “Bar & Grill” to get it over the line, Russell says, brought a lot of what he and Clark had been discussing into crisper focus, and the menu and wine list followed suit.

“We wanted the food offering to be really classic, to focus on execution, and on having dishes that people recognise,” Russell says.

He’s not really the sort of chef who looks to cut corners, so while he’s not looking to reinvent the wheel with the menu, he still puts in an awful lot of work under the hood making sure everything’s as good as it can be, whether it’s enriching the ragù for his rigatoni with beef cheeks or sourcing rolled saddles from Margra for the roast lamb served with braised peas with bacon and shallot.

On the grill, Russell prefers anything dry-aged to be grass-fed and on the bone. When he buys wagyu from 2GR or Westholme he likes the less obvious cuts – chuck tail flap, tri-tip. “And those cuts sell,” he says. “I think sometimes people make the mistake of underestimating customers in Brisbane and what they want, somehow thinking all we want to eat up here is a fillet steak with a lobster on it or something.”

After cooking in Queensland for more than a decade, he says it’s just not how things are. “We sell a really good cross-section from the grill of everything from the high-marble wagyu to the dry-aged grass-fed meat.”

Roast lamb with braised peas, bacon and shallot at Rothwell’s Bar & Grill.

And the runaway success of the Beef Wellington? “It’s ended up more of a feature than we initially intended,” Russell laughs. “I certainly didn’t think I’d be making Wellingtons all day every day, but it’s strangely a dish that everyone seems familiar with.” Familiar, and comforting, he says, even though it’s not a dish common to home kitchens or even that many other restaurants. He estimates that half the people walking through the door ordering a Beef Wellington at Rothwell’s have never tried one before.

It’s a situation that Russell finds rewarding. Taking the focus on reinvention, he says, allows him to put the execution and delivery of the food first. “I’m really happy that everything we do is classical; maybe 15 years ago I wouldn’t have been. But for me at this point in my cooking career and my life, I really like doing this – it’s very satisfying.”

The pleasure and pride in the kitchen at Rothwell’s are felt in the dining room. If the first Beef Wellington of your life is here, with Ben Russell running things chances are it won’t be your last. And hey: the Wellington you order today might end up your go-to comfort dish of tomorrow.