Editor’s Letter

Back to contentsEditor’s

Letter

Welcome to Issue 19 where we explore comfort food and its incredible ability to stir up feelings of sentimentality, warmth and happiness. Often associated with emotional stress, comfort food bounced back in a big way during the pandemic where we saw chefs cooking food inspired by their own notions of comfort and designing menus that appealed to their comfort seeking customers.

As we emerge from Covid’s clutches, the good news is, it seems comfort food is here to stay. Be it specific to an individual or a cultural classic; a childhood favourite (hello crumbed lamb cutlets) or a ‘treat yourself’ craving – the transformative power of nostalgia is informing menus across the country.

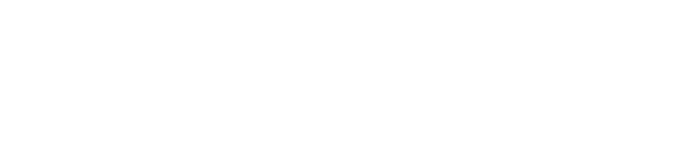

Pat Nourse catches up with chef Ben Russell at Rothewell’s Bar & Grill – Brisbane’s hottest new destination; an ode to the timelessness of the great bistros of the world and the comforting familiarity of menu classics. Here, it is the revival of the Beef Wellington that has taken diners by the hand and the heart – where the combination of time honoured technique is coupled with quality produce and meticulous preparation. The result is comfort at the highest level.

Mark Best reminisces on the warm feelings evoked on the coldest mornings when his mother served savoury mince on hot buttered toast. Around the world, mince has played a similar role in vastly different settings with dishes that transcend time and place, have a hold in history and are lovingly passed down, reinvented, and given new life. Mark explores memories of mince and the comfort dishes it conjures up for Palisa Anderson, Paul Farag, O’Tama Carey and Enrico Tomelleri.

I spend some cherished time at Baba’s Place where nostalgia drips down the walls and weaves its way into every part of the experience – where a menagerie of memories of growing up in Western Sydney are interpreted and elevated in every bite. Here, Jean-Paul El Tom, along with his mates Alex Kelly and James Bellos, are inviting you to experience their memories of food – while reminiscing on your own cherished experiences of food and family. Baba’s Place radiates warmth and familiarity – where you come to get fed and leave feeling part of something much bigger.

Myffy Rigby experiences the ultimate in Winter comfort with a trip to the balmy 32 degree days on offer in the Top End. What’s Good in Darwin uncovers a burgeoning food scene driven by a melting pot of cultures and hyper local produce. Underpinned by institutions like Jimmy Shu’s Hanuman and accelerated by the palette and passion of former Masterchef contestant Minoli de Silva at her first restaurant Ella – Darwin might just surprise you. If the sun setting into the Timor Sea while you indulge in an array of snacks from the Mindil Beach Sunset Market doesn’t fill you with a sense of happiness – I don’t know what will.

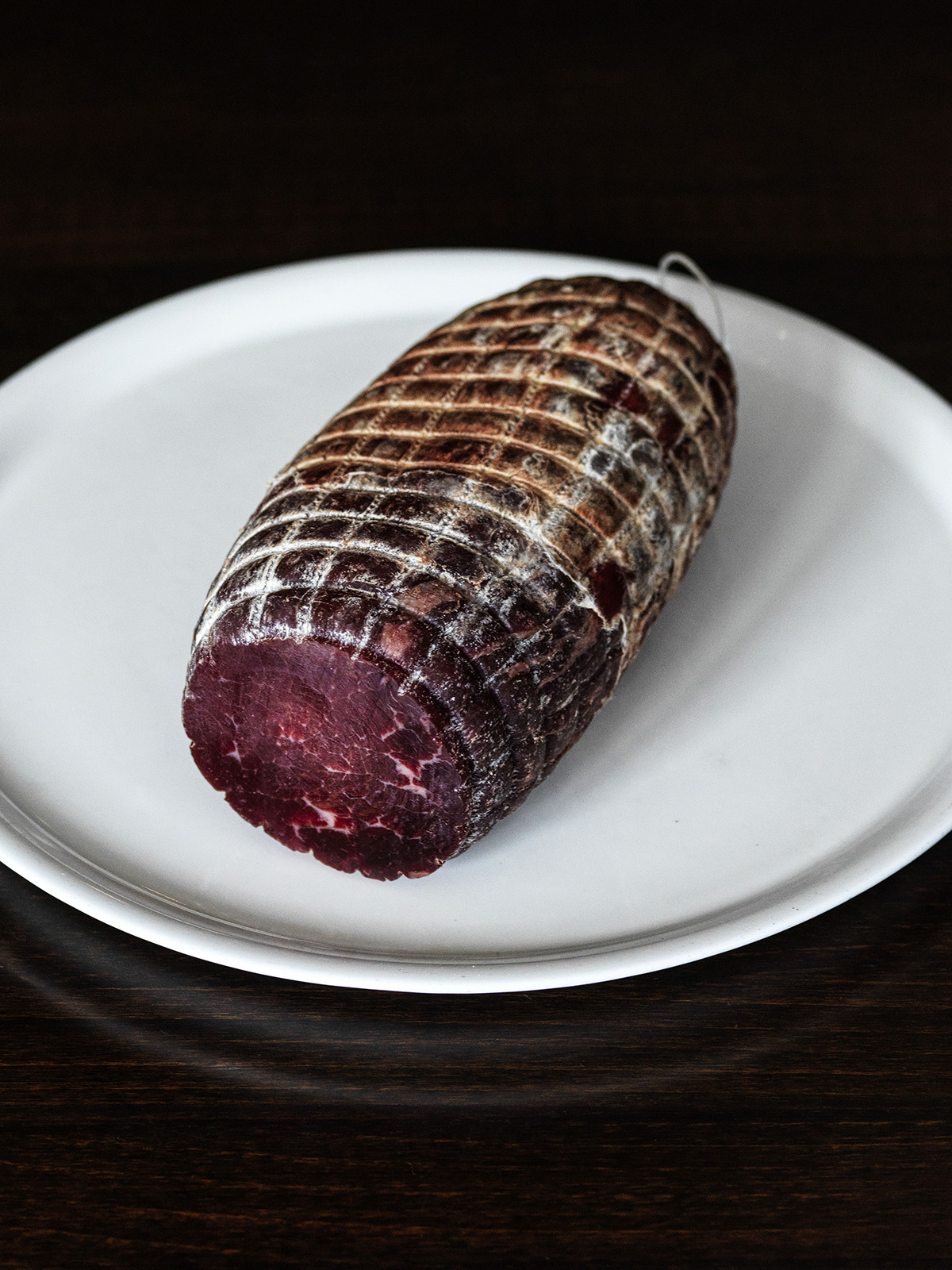

When you take dry aged mince, expertly prepared by Marcus Papadopoulo from Whole Beast Butchery, and put it into the hands of Barzaari’s Darryl Martin and Federico Zanelatto of LuMi, Leo, Ele and Lode – you know you’re going to be rewarded with some mince magic. The boys definitely passed the vibe check on the comfort brief and Cut Two Ways comes alive with Federico’s famed beef pithivier and Darryl’s take on kousa – stuffed Lebanese zucchini.

Finally – is there anyone more deserving of comfort than our loved ones in aged care homes around the country? Estia Health is shaking off the shackles of what we think generally constitutes aged care food with freshly prepared, culturally curated menus that provide residents with comfort and familiarity. Discover an uncompromising level of care for older Australians in this issue’s Big Business section.

Mary-Jane Morse

Meat & Livestock Australia

[email protected]

@_raremedium

Copyright: this publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA).